For much of history, traditional agriculture was characterized by animal traction and diversified farming operations that included crop and livestock components in a mutual and sustainable relationship. The agricultural revolutions and rapid adoption of modern farming broke this mutual relationship and replaced holistic systems with reductionist components. This process terminates today wherein biotechnology replaces nature as the focus of agricultural innovations.

For much of history, traditional agriculture was characterized by animal traction and diversified farming operations that included crop and livestock components in a mutual and sustainable relationship. The agricultural revolutions and rapid adoption of modern farming broke this mutual relationship and replaced holistic systems with reductionist components. This process terminates today wherein biotechnology replaces nature as the focus of agricultural innovations.

Several reports published in the 1980s documented the negative environmental and social impacts of modern agriculture and suggested increased support for alternative and/or organic agriculture. The USDA Report and Recommendations on Organic Farming provided scientific evidence of yield, net returns, and established principles of organic agriculture. (So organic agriculture works? So it would seem.) This report was rejected by the incoming Reagan Administration, which also abolished the Organic Resources Coordinator position in USDA. The combination of these reports provided evidence in support of the need to develop USDA programs in sustainable agriculture research and education that made agriculture safer for humans and the environment and more productive for future

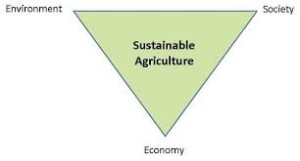

generations. Critics warned that organic agriculture was not profitable and that it could not feed the world‘s growing population. To avoid some of these formidable critics, advocates of organic agriculture began supporting the term ―sustainable agriculture‖ as the proposed alternative to the dominant form of chemical-intensive agriculture. This strategy was successful . Due to extensive lobbying by advocates of alternative agriculture, the 1985 Food Security Act included provisions to support the development of sustainable agriculture. In 1988 the Low-Input Sustainable Agriculture Program (USDA/LISA) was created. The goal of the LISA competitive grants program was to develop and promote widespread adoption of more sustainable agricultural systems that would meet the food and fiber needs of the present while enhancing the ability of future generations to meet their needs and promoting the quality of life for rural people and all of society. An innovative provision of LISA was that farmers must be heavily involved in the program. The organizational structure of LISA was created to accommodate regional practices and research needs. The structure included a national director, four regional coordinators, and in each region an Administrative Council (AC) to set program goals and oversee grants programs and a Technical Review Committee (TRC) to review the grant proposals for scientific merit. The AC was to consist of a broad mix of farmers, LGU scientists, USDA/government agency representatives, agribusiness representatives, and non-governmental organization (NGO) representatives. Congress expected LISA to approach agricultural research from a non-conventional perspective and not replicate the existing USDA programs. LISA was designed to be a science-based grass-roots problem-solving program with major involvement of farmers and NGOs, as well as LGUs, in the management of the program. It was to be a significant departure from the standard or ―business as usual‖ single-discipline, reductionist studies focusing on a small component of the overall farming system. LISA was to support the work of interdisciplinary teams in developing and adopting farming methods and systems that are economically profitable, environmentally sound, and socially acceptable. These three components are referred to as the three legs of the sustainable agriculture stool.

Although Congress lauded LISA‘s innovative work and increased the funding the following year, to deflect criticisms from the chemical industries regarding low-inputs, the FACT Act of 1990 (Food, Agricultural, Conservation, and Trade Act of 1990) changed the name of the program from LISA to SARE, the USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program. Sustainable agriculture was defined as an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having site-specific application that will over the long term: (1) satisfy human food and fiber needs; (2) enhance environmental quality and the natural resources and on-farm resources and integrate, where appropriate, natural biological cycles and controls; (3) sustain the economic viability of farm operations; and (4) enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as whole. As opposed to the top down technology delivery system associated with conventional agriculture and the traditional Extension Service, SARE is built on a participatory research model that values producers‘ knowledge. SARE strives to view farming from a whole-systems approach as compared to the reductionist view of traditional agricultural disciplines. SARE strongly encourages multi-disciplinary and multi-institution research that generates research to enhance environmental quality, economic profitability, and social quality of life. In the same year, the EPA created the ACE (Agriculture in Concert with the Environment) Program. From 1991 through 2001 SARE and ACE funded projects were jointly administered through SARE. SARE budget monies are divided into two competitive grants programs. The Research and Education Program is dedicated to the development of sustainable agriculture innovations/practices. The Professional Development Program is dedicated to ―train the trainer‖ projects with the goal to diffuse the sustainable agriculture innovations/practices from farmers to agricultural educators. A total of more than 3000 projects have been funded since 1988. The budget has increased from the original level of $3.9M in 1988 to almost $19M in 2008, but is still less than one percent of the total research budget in USDA of about $2.3B. (Farmers and ranchers get the short end again.) While there are officially three legs of the sustainability stool, most of SARE‘s projects have addressed environmental quality. SARE‘s focus on environmental issues to the neglect of social and economic equity issues keep it in safer political territory. For some, SARE is only mildly-reformist, too influenced by conventional agricultural through the USDA and the LGUs to be a driver of social change towards substantive forms of sustainable agriculture. So that leaves out profitable and social the other two legs of the stool for sustainable agriculture. We have to develop a complete foundation for our sustainable agriculture. It starts with you as you become more aware of the issues in sustainable agriculture.

Credit for information goes to Douglas H. Constance in his report “Sustainable Agriculture in the United States: A Critical Examination of a Contested Process”